The Aztec legal system was known for its severity and emphasis on public deterrence. Here are the most common crimes and their punishments:

| Crime | Punishment |

|---|---|

| Drunkenness (commoner, 1st offense) | Head shaved, house destroyed |

| Drunkenness (commoner, 2nd offense) | Death by clubbing |

| Drunkenness (nobles) | Death (first offense) |

| Adultery | Death by stoning (both parties) |

| Sexual assault | Death by clubbing |

| Theft | Death by stoning |

| Judicial corruption | Imprisonment, then execution |

| Rebellion | Death by strangulation |

| Attacking merchants | Lord executed, town destroyed |

Exception: People aged 70+ with children could drink freely. Learn more

The Aztec Legal System

General Courts and Judicial Process

The Aztecs had a court system and a legal process similar to how we have one today. There were judges, trials, and sentences.

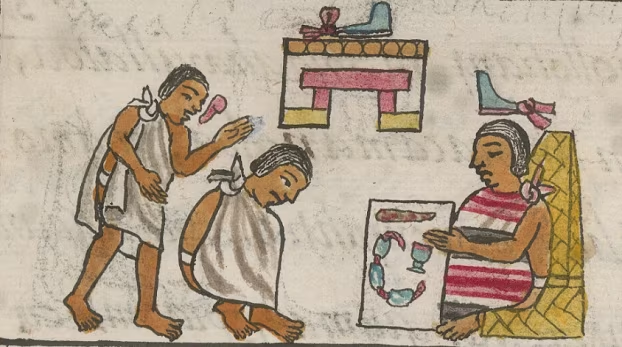

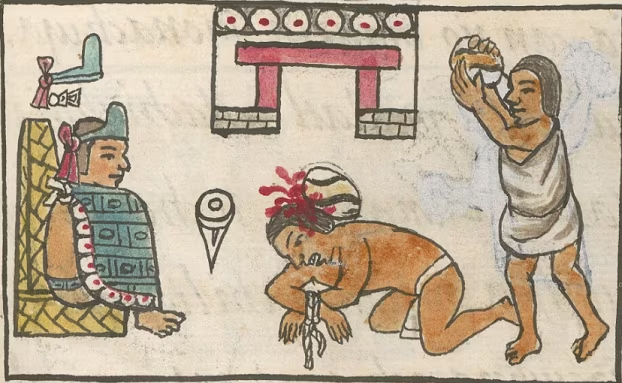

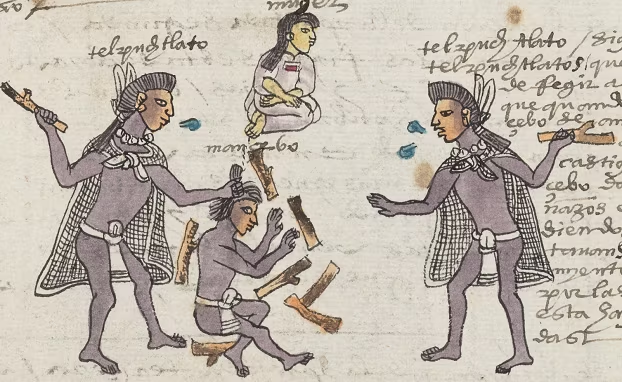

In the below illustration, we can see the judge wearing a headband sitting in a seat on the right holding a sheet of paper.

The guy on the far left with a speech scroll, indicating he is speaking, is likely the plaintiff or a witness, while the guy in the middle sitting on the ground is the accused.

Special Merchant Courts (Pochteca)

The guild of long-distance merchants called the Pochteca had its own judicial system. Unlike commoners or regular royalty, the merchants had unique privilege of self-governance. They were not judged by the state courts but by their own senior members.

They had their own courts because they acted as spies and warriors for the Emperor during their trading expeditions, and because they took the risks of war by entering enemy territory, they were granted the privileges of nobility, including the right to judge and execute their own members.

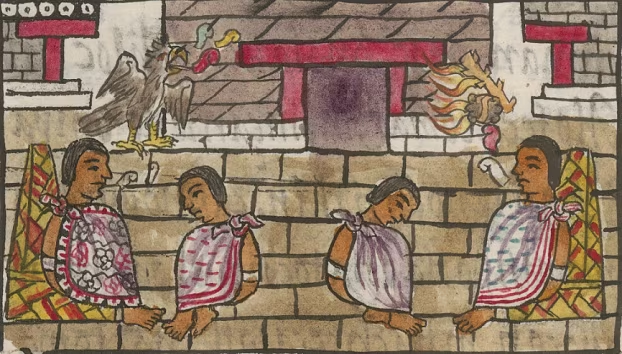

The illustration below depicts a scene from this special merchant court. The 2 men sitting on the left and right are the judges, while the 2 men in the middle are the accused.

The Tlacxitlan (High Criminal Court)

In their high criminal court, called the "Tlacxitlan", they had judges deliver a verdict for the crimes committed along with the method of punishment.

In the below image is a scene from the court. We can see 4 high judges delivering their verdict (designated by the speech scrolls). For the top prisoner, it is death by strangulation, and for the bottom, death by clubbing.

Criminal Offenses and Punishments

Drunkenness

For commoners, if it is their first offense of drunkenness, as punishment, their head would be shaved, and their house sacked and leveled. (Don Fernando De Alva Ixtlilxochitl Tomo 2) For the second offense, they would be punished by death.

For nobles, the punishment was death immediately upon the first offense, as they were expected to set an example and were held to a higher standard.

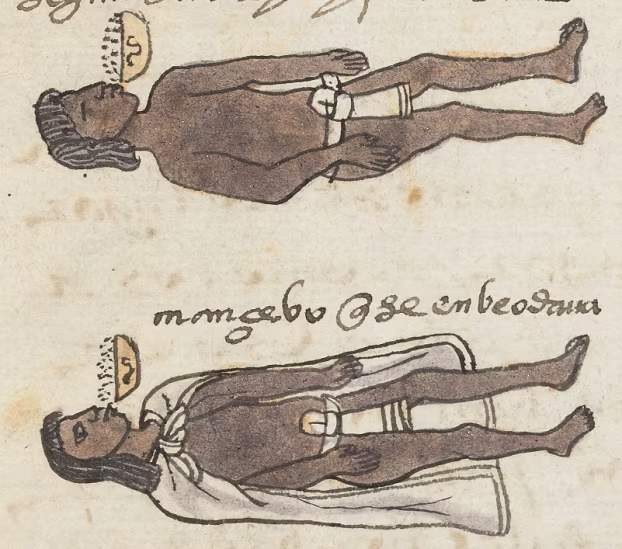

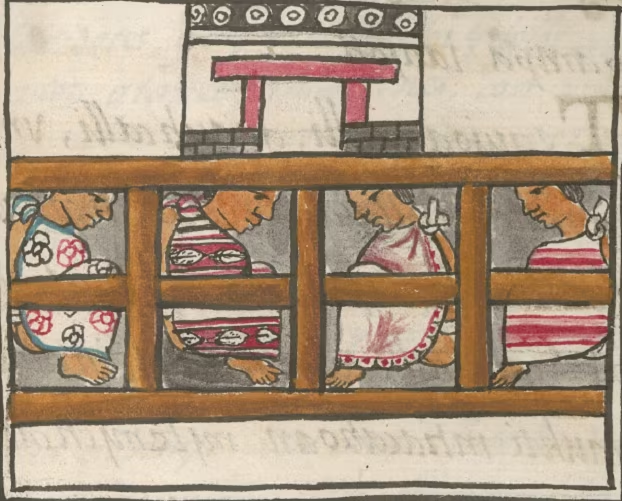

In the below image, we see a couple of arrested prisoners in a wooden cage. In this particular instance, the 2 prisoners were sentenced to death on their second offense for drunkenness.

Prisoners were often kept in custody in these type of wooden cages until their sentence could be carried out.

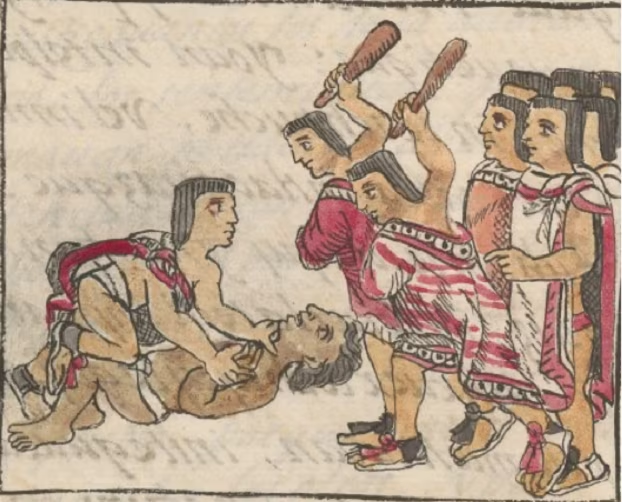

The punishment for such a crime was execution by clubbing. In the below image, we see one of the previously mentioned prisoners being clubbed to death. These executions were carried out in public spaces to serve as a warning.

Exceptions to Drinking Laws

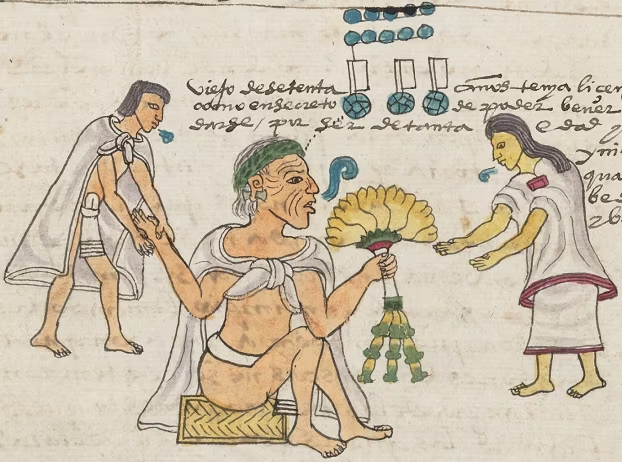

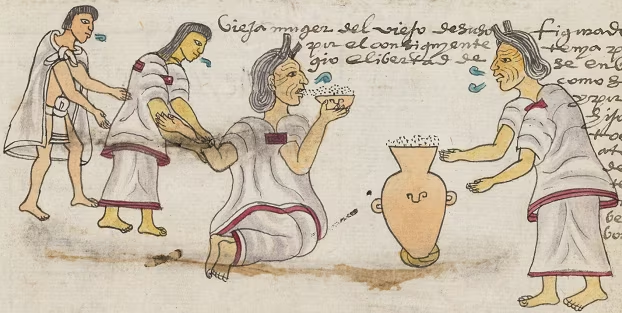

However, there was an important exception to the strict laws against drunkenness. In the below image, we see that an old man at the age of 70, who has had children and grandchildren, has permission to drink wine and get intoxicated in public or private. He was not forbidden from drinking.

Below depicts the wife of the man above. She too was not forbidden from getting intoxicated.

Adultery

If someone was caught cheating on their spouse, both that person and the one they were with were stoned to death.

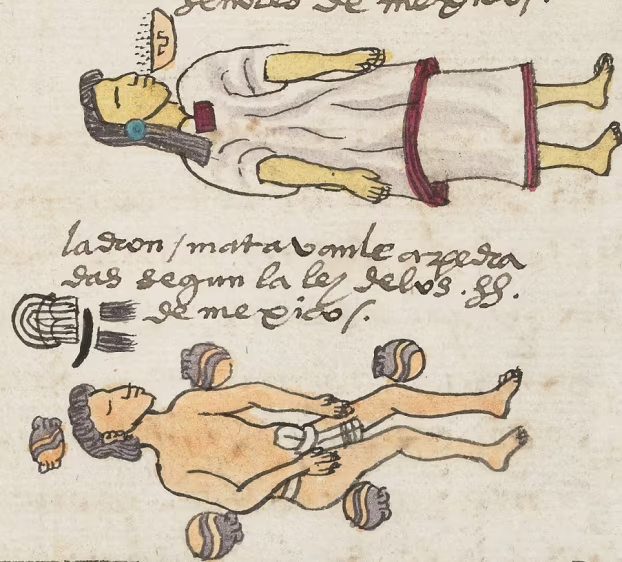

The law applied equally to everyone. In the below image, a noble has committed adultery and is seen getting stoned to death in front of all the people, while the ruler pronouncing the sentence is seen on the left.

Below shows an illustration representing the crime of adultery and the punishment for which would be death of both by stoning.

Sexual Assault

In book 9 of the Florentine Codex, there is mention that when merchants traveled, they stayed together in a single house for safety. And if a merchant sneaked off to assault a woman, they would be punished by death.

The below illustration shows such a punishment. Death by clubbing. In the image, on the right we can see the woman representing the victim. The judge is seen on the left. And in the middle we see the accused getting clubbed by the executioner.

Theft

Below image means the youth who became intoxicated with wine died for it, in accordance to their laws.

In the below illustration, the top person represents a woman getting intoxicated and getting killed for it. And the below image depicts a thief, who would be killed by stoning.

Judicial Corruption

Judges who failed to perform their duties honestly in the judge's hall would face severe consequences.

In the below image, it depicts judges that were accused of unreasonably delaying lawsuits (sometimes for years) or accepting bribes and favoring relatives.

As punishment, they would first be jailed in wooden cage (depicted in the below image) before eventually being executed.

Rebellion and Attacks on Merchants

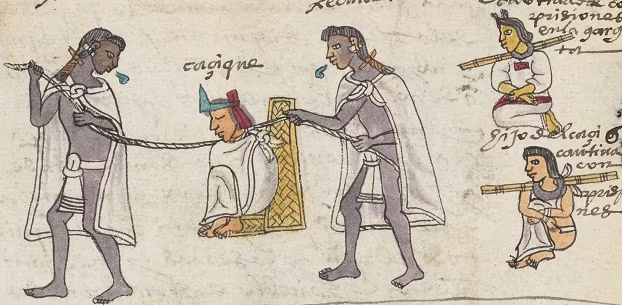

If a lord of a town rebelled against the lordship of Mexico, he would be condemned to death by the lord of Mexico, and his wife and children would be captured and taken prisoner to the court of Mexico.

We see the arrested lord in the middle with rope tied around his neck. The punishment is death by strangulation. And to the right we see his wife and child that have been taken prisoner.

The below depicts the crime being committed. The 2 men being stabbed by pikes are merchants. They were ambushed and killed by townspeople in this image. The punishment for such actions is the lord as we saw above would be strangled, and entire town is destroyed, and everyone in it. It is almost considered an act of war, so the punishment is severe.

Discipline and Punishment for Children

One of the things parents wanted their children to avoid was idleness so they can avoid bad habits that can come from idleness. From birth to the age of 7, it was mostly about teaching the child to be productive with household tasks.

Age 8: Warnings and Threats

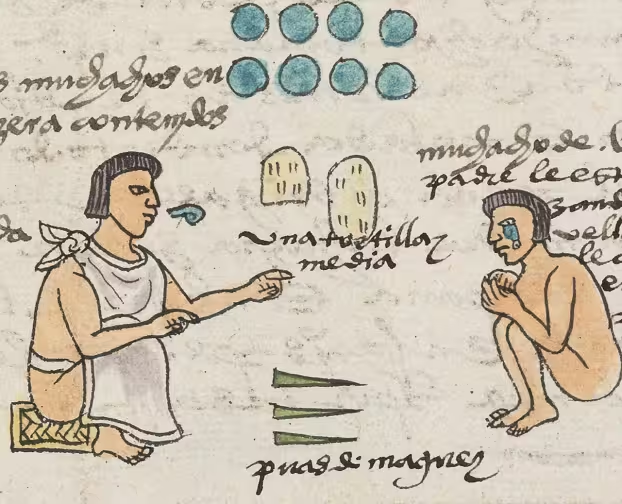

At the age of 8, that is when the parents would start to explain to the child of the consequences of being disobedient. They did this by showing the child maguey thorns, and that they would be punished by the use of those thorns.

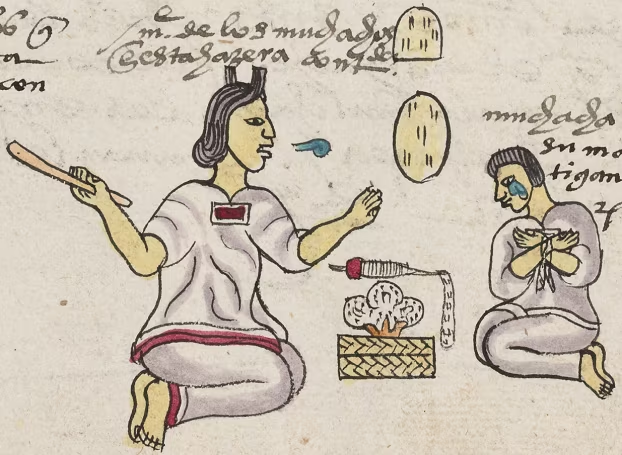

The below illustration shows the father of an 8 year old boy. The father is on the left talking to the boy on the right about the thorns on the ground being potentially used for disciplinary reasons. The boy is seen crying in fear. (the 8 green dots above them represent a counter for the years of the age of the child, and the oval shaped objects in the middle represent tortilla rations for the child, in this case 1 and a half tortilla)

And in the illustration below, we can see the same concept, but with a mother and her daughter.

Age 9: Maguey Thorn Punishment

At the age of 9, if the child is disobedient or rebellious, they would punish the child by using the maguey thorns.

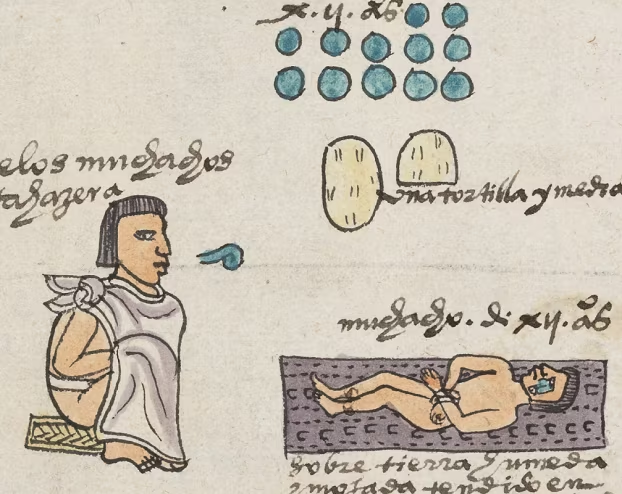

For boys, they would tie his hands and feet with rope, and stick the thorns on his body as is shown in the illustration below.

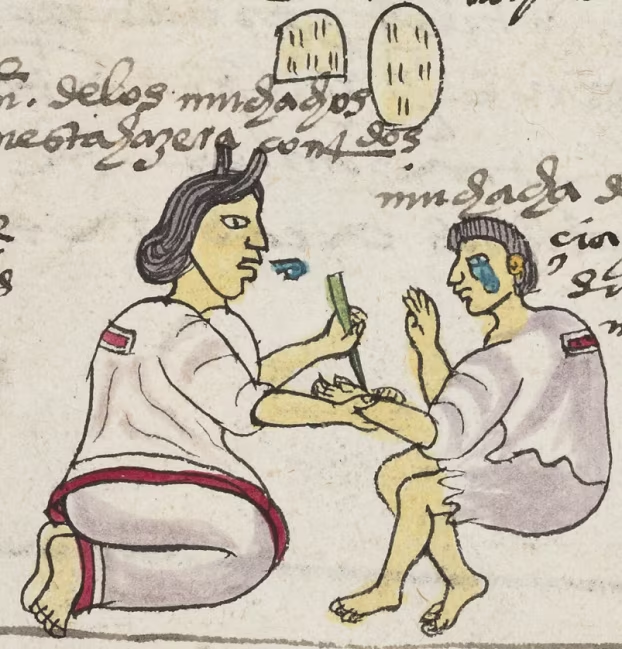

For girls, the punishment was a little milder as they only pricked her hands with the thorns as is seen in the below image.

Age 10: Beating with Sticks

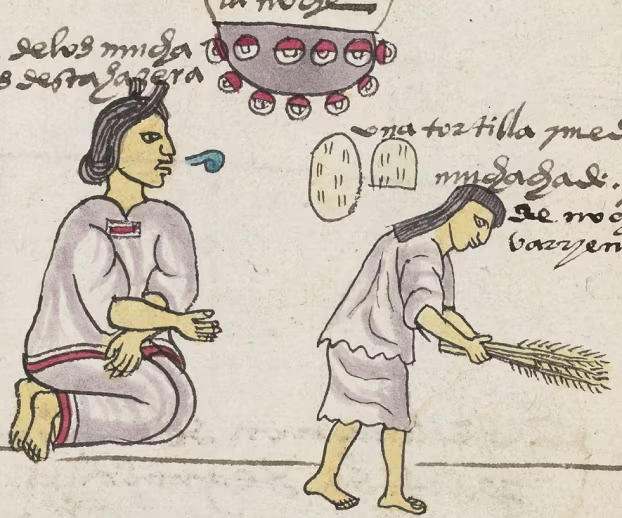

At the age of 10, they punished them by beating them with sticks. In the below illustration, we see a boy getting punished with a stick.

Same punishment shown below for a girl.

Age 11: Chili Smoke Inhalation

At the age of 11, the punishment was inhaling chili smoke. In the below illustration, we see the father holding the boy over the burning chilis.

And here we can see the mother doing the same to the daughter.

Age 12: Final Disciplinary Measures

At the age of 12, for boys, the punishment would be to tie their hands and feet, and lay them on damp ground.

And for girls, they would make her sweep the floor.

Rules and Punishments for Young Priests

Punishment for Negligence

Novice priests in training would be punished if they were careless or negligent in a duty. Their punishment is similar to how children at age 9 were punished, with maguey (agave) spine.

Below, we see a senior priest (seated, with dark skin paint and a speech scroll indicating authority) is piercing the arm of a crouching novice with maguey spine as punishment for negligence.

Severe Punishment for Truancy

And below, depicts a much more severe punishment. Two senior priests are holding a novice standing up while sticking maguey spines into his torso, arms, and legs.

Below them is a small glyph of a head peeking out of a box/house with 3 dots. The students in the Calmecac were expected to sleep at the school. If a student snuck away to sleep at his parents' house (represented by the "casita" glyph) for three days, he was considered "incorrigible" and subjected to this severe stinging punishment.

Breaking Vows of Celibacy

In boy's school, celibacy is required. The typical life for a male is going through boy's school, and then once he is old enough, gets married, or joins the warrior ranks. Any illicit sexual relationship outside of marriage is punished.

They separate the couple by punishing the male. In the below illustration, we see the 2 commanders in charge of youth / head of the school grabbing the hair of the youth and beating him with wooden sticks that are on fire. It was a painful punishment designed to leave a visible mark, reinforcing the severity of breaking the moral code.

If a novice priest became negligent, or had sexual relationships with a woman, or got drunk, the major priests punished him by inserting pine spines or sticks through his entire body.

In the image below, we see just that. The presence of a woman in the illustrations indicates the specific sin committed, breaking the vow of celibacy. The high priests are inserting pine needles all over the body of the novice priest as punishment.

Punishment for Vagrancy

For being a vagabond, the punishment was burning of the hair. Even though it may seem like a mild punishment, and equivalent to a free haircut, but in Aztec culture, it was devastating because the hair style was a status symbol. To have your hair shaved or singed publicly was to be stripped of your status.

It signaled to everyone that you were not a warrior-in-training, but a failure or a "nobody." It was a punishment of intense public humiliation designed to correct behavior through shame.

In the below illustration, we see a youth who was supposed to be in training for war but was caught wandering the streets (often implying drunkenness or avoiding work) was bringing shame to his school and district being punished.

The two officials are seen holding the youth down while one of them is burning his hair with a hot stick (pine torch).

Understanding the Codex Mendoza

This video provides a broader look at the Codex Mendoza, including its depiction of daily life, education, and the strict upbringing of Aztec children.

It features Dr. Daniela Bleichmar explaining the Codex Mendoza's role in documenting Aztec society, which helps contextualize why these specific punishments and social rules were recorded for the Spanish King.

Sources

- Florentine Codex by Bernardino de Sahagún - Getty Research Institute Digital Collection

- Codex Mendoza - Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

- Don Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl - Obras Históricas, Tomo 2 - Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes